Tourism in the Arab World An Industry Perspective (2017)

This book is the first to explore Arabic tourism from a business viewpoint, rather than taking a sociological, anthropological or political stance. It focuses on business planning, management and marketing destinations in the Arab World, which are topics crucial for industry stakeholders and which have previously been neglected in the tourism literature. The book examines similarities and differences in the emergence and development of the tourism industry in countries across the Arab world as well as its inbound and outbound travel flows. It analyses several different aspects of Arabic tourism including tourism policy, organisation and planning, tourism product development, destination marketing and consumer behaviour. This volume will be of interest to postgraduate students and researchers of tourism studies, business and Middle Eastern studies.

click here to buy it from Amazon.com

Planning for Tourism in Oman based on Lessons from Dubai (2017)

By Ammar AlBalushi and Nicholas Wise

Abstract

The Gulf Cooperation Countries have witnessed a rapid surge in tourism developments. Dubai stands at the forefront of this development, a state that is diversifying its economy by investing in tourism to decrease its dependency on oil resources. This economic model carried out in Dubai has become a foundation for tourism planning in neighbouring countries such as Oman, however it is just as important to focus on environmental and socio-cultural impacts as well. In reviewing tourism impacts observed in Dubai, there are a number of lessons that can be learnt by Oman. Dubai is a destination that has experienced the full extent of this cycle, this supports why Dubai is a useful case to consider when outlining lessons and comparisons for Oman. In the case of this chapter, this model will be useful to consider in future research on Oman once the industry is further established and sees growth. At this stage it is important to address and outline impacts based around the triple bottom line framework by discussing economic, environmental and then socio-cultural impacts. Findings offer insights into the defining qualities of Dubai’s tourism model which will provide a number of managerial implications for the Omani policy makers when developing tourism in the country.

Introduction

Understanding the impact of tourism is crucial for governments to execute sustainable tourism development plans. More importantly, policy makers, managers and stakeholders should understand how residents perceive the benefits and drawbacks of tourism and seek ways to involve residents in tourism so that business opportunities are maximised and new tourism products developed. Yet, despite the substantial and the on-going research concerning the impacts of tourism in various destinations, it is important that economic, environmental and socio-cultural impacts are assessed. Given Dubai’s position and growth in the events, tourism and hospitality industries (Sharpley, 2008), there is a need to outline development in relation to the triple bottom line concepts since the destination stands out in the Gulf Region. This chapter looks at the case of Dubai to outline point of tourism development to inform tourism planners in Oman. Oman is regarded as an emerging destination, and it is essential to overview particular impacts as the country develops and expands its tourism industry and infrastructure. It is important that Oman develops a tourism industry that is not only economically sustainable but also promotes business and management agendas that have a positive impact on the local populations socio-cultural values and also protects the environment. Each of these points link to sustainable development and business practices to ensure future growth that sustains impacts for residents. By looking at Dubai, the approach used in this paper is to first explain Dubai’s economic, environmental and socio-cultural impacts of tourism by outlining findings from the literature and reports. After the discussions of Dubai based on each component, the focus will then shift to Oman to assess the current scenario there in relation to achieving a sustainable tourism future. Since more research is needed on Oman, this chapter represents the first stage in our research by outlining research on tourism, sustainability and development.

Though geographically small, the Emirate of Dubai is one of the fastest growing and diversified economies in the region. Moreover, Dubai has established itself as prominent financial and tourism hub of the Middle East with a large migrant workforce from around the world to support and fulfil the city’s multi-sector economy. The adaptation of tourism development and tourism enterprise growth by the Dubai government is a key part of the city’s economic diversification plan that has attracted foreign exchange benefits and has generated new employment opportunities. Thus, Dubai represents a point of assessment to compare approaches in relation to neighbouring countries such as Oman, where tourism is seen as a solution for its low oil production and the growing unemployment levels. While Dubai is an Emirate within the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Oman is a country, these two cases still represent a point of unique analysis. Foremost, Dubai is a well-regarded destination in the Middle East and development approaches are important to assess as a means of gaining from lessons of tourism planning and development. Additionally, Dubai is politically independent and controls its own budget in a similar manner as Oman would as a country. It must be noted that many of the figures presented below do come from UAE databases but are contextualized to refer to Dubai. This chapter will now discuss tourism based on triple bottom line components by addressing economic, environmental and socio-cultural impacts.

Tourism Development and the Triple Bottom Line

Tourism development has been promoted as a force for positive contributions to attract foreign investments, creating employment opportunities, improving transportation systems, promoting local entrepreneurship, creating a new modern way of life, and promoting peace by bringing people of different nationalities and cultures together (Sharpley & Telfer, 2002; Shaw & Williams, 2002). In contrast, like many other sectors, tourism also leads to negative impacts such as changing local cultural habits and place heritage, intruding on local social life-styles, and affects the environment and quality of life through increased traffic, crime, security risks, rising rent costs and inflation (Butcher, 2014; Brida, Disegna & Osti, 2011; Brunt & Courtney, 1999). The outline of this chapter below revolves around the three impacts outlined in the triple bottom line. Subsequent sections the focus will be on economic, environmental and socio-cultural impacts in Dubai and Oman and will identify two or three points linked to each impact (see Figure 1). Extended from each impact are some of the main points outlined below (i.e. economic impacts focusing on immigration, income and jobs).

The triple bottom line is a framework that helps inform tourism planners, developers and managers. The triple bottom line approach attempts to address the impact of not only financial and economic issues, but also on people (referring to social benefits and burdens) and the planet (by discussing growing concerns particular industries such as tourism and hospitality have on the environment) (see Dwyer, 2005; Elkington, 2004). These are commonly referred to as the three Ps: people, planet and profit. John Elkington, a leader in corporate responsibility and sustainable development, coined the term triple bottom line in 1994. This thought has since been embedded into tourism development, product development and business approaches. The ‘Bottom Line’ refers to an accounting framework that point to profits and loss, revenue and expenditures (Dwyer, 2005; Elkington, 2004; Norman & MacDonald, 2004). While this is the case in the corporate business environment, it is also relevant to the tourism industry because there is much concern in the place where tourism developments and enterprises are occurring (Dwyer, 2005).

When outlining observations and attempting to gain lessons based on impacts and examples in other destinations, the triple bottom line framework is used to evaluate different dimensions of sustainability. Sustainable issues are becoming more evident when evaluating ethical business practices framed around principles of responsible management and corporate social responsibility (Goodwin, 2011). The United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) is concerned with founding and establishing wider frameworks to maximise the impact of tourism around the world. The initiatives put forth by the UNWTO are meant to be adapted by national, regional and local tourism organisations and stakeholders to monitor results and business practices concerning the three areas. There have been other approaches used to assess tourism growth and development, such as Butler’s lifecycle model (see Butler, 2006). This generalised model considers seven stages of development: (1) exploration; (2) involvement; (3) development; (4) consolidation; (5) stagnation; (6) rejuvenation; and (7) decline. The seven stages identified is useful after an evaluation of impacts and is useful in determining longitudinal impacts as a destination develops, matures and then regenerates. Outlining observations based on a triple bottom line approach in the case of Oman links to the first three points. Whereas Dubai is a destination that has experienced the full extent of this cycle, this supports why Dubai is a useful case to consider when outlining lessons and comparisons for Oman. In the case of this chapter, this model will be useful to consider in future research on Oman once the industry is further established and sees growth. At this stage it is important to address and outline impacts based around the triple bottom line framework by discussing economic, environmental and then socio-cultural impacts. Following a brief outline on each impact, examples from Dubai are presented followed by an assessment of Oman.

[FIGURE 1 ABOUT HERE]

Economic Impacts

Developments for the tourism sector often focus on achieving economic benefits (Henderson, 2014). The tourism sector is an organism consisting with various establishments, which provide a wide range of services and products for the tourist to consume. Economic impacts of tourism depend on tourism expenditures, concerning how much money they inject into the host economy (Spirou, 2010; Webster & Ivanov, 2014). Therefore, tourism’s main positive impact in a host destination can be measured by the improvement in the national income (Huh and Vogt, 2007) and increased employment levels (Choi, 2005; Diedrich & García-Buades, 2009). From these points, it must be noted that tourism can also have many adverse economic impacts such as increased prices for locals and more reliance on imports to cater to visitor wants and needs. Many industries in the supply side rely on the tourism industry so the impact can be much wider if more people are involved directly and indirectly (Butcher, 2014).

Economic impacts of tourism on Dubai

The economic development of Dubai supports evidence of how tourism contributes to the economy. The tourism sector has helped Dubai achieve commercial diversification by becoming the world’s 8th destination in terms of international overnight visitor spending, which was estimated at $10.4 billion dollars in 2012 (MasterCard, 2013). Moreover, a UNWTO (2013) report indicates that the UAE attracts approximately 18 percent of the international visitors in the Middle East and 22.1 percent of the international tourism receipts–most of that is reflected from the performance of Dubai’s tourism which contributes to 20-30% of the UAE’s total GDP. With regards to demographics, in 2013, the UAE had the 14th highest population growth rate in the world, constituting a 2.87 percent annual change. Much of this change resulted from migrants flow to the country—mainly to Dubai (UNWTO, 2013). According to the UAE National Bureau of Statistics (2010), the vast majority of the population are males (76 percent), with non-nationals dominating 90 percent of Dubai’s population—making Dubai the most culturally diverse Emirate. However, the official statistics were not completely accurate, as it did not assess in identifying the exact definition of tourists and residents as many traders split their time between their home country and Dubai. However, and in general, as a consequence of the acute imbalances, the high flow of temporary non-national residents and their domination over the economy does affect the nationals as it raises significant debates about crime rates, cultural identity and nationalism.

For Dubai, the tourism sector is the largest catalyst and major driver of employment, income and entrepreneurism. Yet, despite the large investments in the tourism sector, which represents 14 percent of the total GDP, and the creation of 523,000jobs in 2014 which is 5.3% percent of the total employment in UAE (WTTC, 2014). The tourism sector in Dubai has the poorest record of Emiratisation. Emiratisation is known as a policy initiated by the UAE government to employ its citizens in the public and private sectors. This can be noted from the level of locals working in the tourism sector as they represent less than one percent of the total tourism sector posts (Alserhan, Forstenlechner & Al-Nakeeb, 2010). Consequently, this results in leakage of payments due to the high number of salary transfers outside the country and the number of franchised hotels, cafés, restaurants and products demanded by tourists and imported from overseas (Gerson, 2009; Stephenson & Ali-Knight, 2010). Moreover, there is no reliable official figure found for ‘leakage’ in Dubai or the UAE. However, Dubai’s demographic imbalance and high level of foreign ownership can provide an indication on the alarming issue caused by immigration and leakage of economic surpluses resulted from tourism development (Meethan, 2012).

Economic impacts of tourism on Oman

Given the rapid growth of Dubai, Oman’s tourism sector is considered at the inception stage. This can be concluded from its total contribution to GDP which was 2.2 percent in 2014 (NCSI, 2015a). Differing from Dubai, non-nationals in Oman represent 44.4 percent of the total population (NCSI, 2015b)While the tourism sector in Oman contributes to 3.3 percent of the total employment (96,000) in 2013, the locals represented 7.5 percent of tourism’s total employment (Ministry of Manpower, 2013). In the case of Dubai, the section above highlighted Emiratisation. Similarly, in Oman, Omanisation is a policy executed by the government aimed at replacing expatriate workers with trained Omani Personnel. The government set quotas for every sector to reach in terms of the percentage of Omani to foreign workers. It is important to note that despite the high Omanisation quotas applied by the government on tourism establishments (i.e. reaching 85 percent), continued limited employment among nationals in the tourism sector is seemingly a social concern. A survey conducted by the Omani Ministry of Tourism indicated that high Omanisation quota and the lack of interest by locals in joining the tourism sector are the main obstacles among the key obstacles facing the growth of tourism in Oman (Pourmohammadi, 2014). This lack of interest especially could impact local tourism enterprises which would result in more demand for a migrant labour force. Pourmohammadi (2014) indicates that the lack of interest by the locals is attributed to the low salaries, long working hours, job securities and annual holidays, when compared to the public sector. More importantly, the survey results in Oman are compatible with the Emiratis lack of interest in working in the tourism sector (Stephenson & Ali-Knight, 2010; Sara & Samihah, 2013). However, no study in Dubai or Oman was found proposing a method to tackle the employment issues within the tourism sector.

Environmental Impacts

The relationship between the environment and tourism is relatively complex because the environment represents an important resource, which needs to be protected in order to nurture the economic progress of a destination (Gössling et al. 2012). Tourism development induces both positive and negative environmental impacts due to the constant development of infrastructure, which contributes to air and water pollution and impacts on local populations (Dwyer, 2005). The positive environmental impacts of tourism involve planning and executing ecological development in the national economic plans, recreation of parks and stimulation of environmental conservation (Baysan, 2001; Phillips & Moutinho, 2014). Thus, positive environmental enhancement through tourism might lead to better economic support to modify and control recreational structures such as restoration of historical sites, antiques, marine and wildlife, and opening up new forests and lakes for tourists (Baysan, 2001). In contrast, negative environmental change caused by the increase number of tourists (Cohen, 1979) can lead to water shortage, pollution and littering (Frauman & Banks, 2011).

Environmental impacts of tourism on Dubai

The philosophy of tourism development in Dubai is arguably based on becoming ‘bigger and better’ than the rest of the world (Sharpley, 2008). In his work, Sharpley (2008) notes that the fundamental objective of Dubai’s philosophy is to create a unique brand based on shopping and entertainment experience. Creating such an environment can, however, have environmental consequences given the dependence on creating climate controlled environments. Moreover, there is no publicly accessible information on Dubai’s economic expansion and impacts, likely due to the existing governmental restrictions (Nassar, Blackburn & Whyatt, 2014). However, various resources did report shortage of land in the coastal and urban areas of Dubai due to the rapid land transformation through expansion in development and construction of hotels. Taleb and Taleb’s (2014) study on the thermal comfort on Dubai’s urban and desert areas have indicated that economic development such as hotels, parks, creeks and yacht ports had a positive impact on the environment due to the increase in vegetation. However, the same study showed that tourism developments can increase electricity consumption and alteration of coastline. Moreover, Al-Mehairi (1995) indicated that developments in Dubai contributed negatively to its desert ecology and consequently increasing its road traffic, congestion and air pollution. It is important to note that Dubai airport is located in the centre of the city and thus, considered a source of noise and air pollution. Much of the debate on Dubai’s environmental impact revolves around how rapid urbanisation and modernisation developments can harm Dubai’s heritage conservation, wildlife, beaches and natural resources. Stephenson and Ali-Knight’s (2010) found that Dubai is losing its built heritage at the rate of one historic building a day. Hence, losing heritage resources that reflects Dubai’s history in favour to the modern westernised buildings which are seen as disconnected from the Emirati culture.

Nassar et al. (2014) argues that offshore and onshore construction of developments in Dubai such as Jeremiah beach, the palm islands, creek dredging, port construction and development of recreational water bodies show considerable alteration to the form of coastline. These large changes can have a direct impact on the environment due to the continual inputs of energy and chemicals used to maintain the land. Legislation has been passed in order to resolve these issues in Dubai, but scholars argue that more policy is needed to protect the environment around the world in popular tourism destinations that promote ecological and social benefits (Taylor & Hochuli 2015). Hence, what the literature does not explain is why the authorities in Dubai did not provide any solutions for the environmental issues caused by tourism and the economic development. Perhaps, Sharpley’s (2008) analyses of the nature of the authoritarian political structure in Dubai and the neighbouring states in regards to the planning and decision making process, can explain why most of the tourism and environmental decisions, if not all, are made by the ruling regime and are based solely on the economic benefits of tourism. Similarly, Krane (2009, p. 224) states “when the top guy in the country is a major investor and major player, people get away with a lot in his name”. The author further adds projects developed by high ranking officials in Dubai have ignored sustainable environmental measures and therefore resulting in numerous investors ignoring them too. Thus, pressing issues pertinent to environmental sustainability have resulted in a primary focus on the economic development in Dubai. This represents an important lesson for Omani policy makers, and having a clear and sustainable environmental agenda is needed ahead of the tourism planning/development strategy.

Environmental impacts of tourism on Oman

Despite the similarities with Dubai’s political structure, Oman’s ministry of tourism focused mainly on the diversity of its landscape, and heritage and monument conservation. In 1984, Oman became the first Arab state to create a ministry dedicated to issuing environmental policies and conservation laws. Moreover, satisfying all the environmental requirements by acquiring permission from the ministry of environment to construct any tourism development is obligatory before starting any project (Ministry of Tourism, 2015). Oman enforces strict environmental planning regulations to protect and preserve environmental resources that developers and businesses need to adhere to (Minsitry of Legal Affairs, 2001). Furthermore, the ministry of environment has transformed various environmental sites such as Al Hota Cave, Wadi Bani Khali, Wadi Shab, and traditional suqs and protected endangered wildlife by establishing nature reserves such as the turtle breeding beach at Ras Al Hadd and Ras Al Jinz, the bird sanctuary at the Diymaniyat Islands and the Arabian leopard at Jebel Samhan. It is important to note that killing and hunting wildlife in Oman is strictly prohibited and carries stiff penalties (Ministry of Legal Affairs, 2001). Hence, Oman uses its environmental diversity, conservation and heritage as brand in marketing and attracting tourists (Ministry of Tourism, 2010). However, the analysis on Dubai did highlight some environmental issues in regards to the Omani current development. Krane (2009) indicates that the approval of transforming an area and building a luxury hotel on the beach in Oman has critically endangered hawksbill turtle. Moreover, similarly to Dubai, the transformation and development process in Oman has decreased the nesting pairs of an extremely rare subspecies white-collared kingfisher. However, the lack of reliable studies on the impacts of tourism on the environment in Oman puts emphasis on the importance and need to examine this topic in greater depth to highlight knowledge gaps and put forward strategies that can help achieve sustainable tourism.

Socio-Cultural Impacts

Socio-cultural impacts of tourism are unavoidable, and positive results contribute to the longer-term success as a destination grows (Butcher, 2014; Deery, Jago & Fredline, 2012). Some argue that without tourists, local cultures and traditions may have been lost completely; alternatively, tourism encourages the commodification of culture (Schelling, 1998; Xie, 2003). Tourism initiates contact between two groups of people: tourists and locals. Tourists and locals often differ socially and culturally (i.e. religion, language, race, ethnicity); but it is tourism opportunities that bring people together who might otherwise not meet. Tourism involves social and cultural exchanges between the host and the guest. Pizam and Milman (1984) noted that socio-cultural impacts of tourism include changing the hosts value system, behaviours, family relationships, lifestyles expressions, traditional ceremonies, and community structure. From this, Pizam and Milman (1984) identified six main categories of socio-cultural impacts which are: (1) demographic, such as size of population, age and pyramid changes; (2) occupational, referring to the frequent change of jobs and distribution of jobs; (3) cultural, linked to religion, tradition and language; (4) transformation of norms, such as values, morals and change in gender roles; (5) modified consumption patterns, such as new infrastructures and commodities; and (6) environmental impacts such as pollution and traffic congestion.

Generally, the literature has addressed a range of perspectives in relation to the above, including, crime (e.g. Diedrich & García-Buades, 2009), traffic, pedestrian congestion and noise (e.g. Deery et al., 2012), pollution (e.g. Brida et al., 2011) and drugs and prostitution (e.g. Kanna, 2010). For the cases of Dubai and Oman two socio-cultural impacts are explored. These include the modification of local culture (demonstration effect) and language. Wall and Mathieson (2006) defined demonstration effect as the introduction of new foreign behaviours, pattern, values, attitudes and life style in a community that has not been exposed to it before. This concept can exist by observing tourist lifestyle and the subsequent urge to copy their values, attitudes and behaviours. The demonstration effect can be perceived as a positive impact if it motivates locals to work on delivering new tourism products (Wall & Mathieson, 2006). However, the literature mostly argues that the demonstration effect is mainly perceived negatively as it can encourage host communities to consume commodities that they would not normally, such as consuming imported products rather than the locally produced versions—this can lead to economic drain and social decline in other sectors. Furthermore, demonstration effects can create divisions and conflicts among locals between those who want to adopt foreign values and those who want to maintain traditional values. Thus, this can create social and political tension, especially in traditional and developing countries such as the Middle East, where conservative and religious values are present—this can hinder the social development of tourism (Farahani & Musa, 2012).

Socio-cultural impacts in Dubai

Dubai has experienced this demonstration effect as a result of the high migrant population who are working in the city and increased tourism due to the expansion of the Emirates airline hub. An interesting example of this can be found in Ali’s (2010) analysis of the Emirates national identity, as he argues that the presence of so many expatriates is leading to the loss of national identity and culture. Ali’s (2010) study illustrated identity issues facing local Emiratis, and concerns linked to how to preserve their local culture, values and norms despite increased foreign influences. 2008 was a ‘National Identity Year’ in the UAE, which attracted heavy national and international attention and contributed in publishing various articles discussing the threats facing the Emirati identity and culture. While Ali’s (2010) definition of expatriates did not differentiate between the workers, residents and tourists, it is Dubai’s extensive investments in tourism development that are causing these socio-cultural implications. An implication mentioned by Kanna (2010) is that Dubai is emerging as a sex tourism destination in the Middle East. Despite prostitution being illegal, adultery is an impressionable offence and public ‘overt displays of affection’ such as kissing are strongly discouraged, the government ignores the imported prostitution from Eastern Europe, Asia and even the UK (Butler, 2010). Kanna (2010) also indicated that the availability of prostitution and alcohol in Dubai is caused by diversifying economic opportunities in the service sector. Furthermore, the same study indicates that the locals are unhappy with amount of development of tourism in Dubai due to the socio-cultural implications associated (Kanna, 2010).

The literature also argues that introducing foreign languages in host communities can cause distortion in local languages (Ali, 2010; Sebastiana & Rajagopalana, 2009). In Dubai, as noted above, the local population is the minority and the overall population is the most diverse in all of the UAE. Ali (2010) argues that the Arabic language is declining significantly in the UAE due to the decline in using Arabic language in public life. The decline in fluency of younger generation in written and speaking Arabic is becoming more apparent. According to Ali’s (2010) analysis, this distortion is caused by the use of English language in media, schools and social contact with tourists and workers in Dubai—who represent approximately 90 percent of the total population. However, tourism can not only be blamed for the alteration in local languages, as television, social media, the internet and local frequently interacting with foreigners are important elements influencing the local communities to change their local languages.

Socio-cultural impacts in Oman

Oman’s economy, like Dubai, is strongly dependent on short term foreign labour to build its infrastructure (Ministry of Manpower, 2013). Unlike Dubai, however, the tourism projects, the number of tourist arrivals and foreign labour is significantly lesser. Because tourism arrivals are less in Oman compared to Dubai, socio-cultural impacts (such as demonstration affect) has not yet been studied in Oman and will be a point of future research as tourism increases to evaluate cultural impacts and adaptations to tourism. However, some of the notable sociocultural ramifications in Oman are the increase in number of expatriate workers on which its economy relies; for example, almost half of Oman’s 4 million residents are foreigners (The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2014). Further, heavy investments in tourism enclave projects such as the Wave Muscat, Muscat Golf and country club and Al Salam Yiti were fuelled by the Dubai real estate model (Amrousi & Biln, 2010). Such projects aim to provide direct interactions between expatriates and locals living residing in new estates. Consequently, this may result in influencing the local youths to copy the behaviours and spending patterns of the tourists and foreign residences—referring back to the demonstration effect and foreign influence on local culture.

Development processes have inevitable impacts on the society’s values and culture—thus tourism represents a channel for development and diversification. Accordingly, this issue raise important questions concerning the socio-cultural impacts of tourism on the Omani residence, how to measure them and plan a sustainable tourism receiving society with minimum adverse societal impact. The impacts observed in Dubai are a challenge to the future socio-cultural sustainability so Oman as an emerging destination can learn from what has occurred/is occurring in Dubai as the UAE and Oman share a lot of similar cultural and religious values.

Language is the main element representing the national identity and is the main contributor in successful transcultural communications between tourists and locals. Semela (2012), for instance, attempted to understand how socio-cultural impacts of tourism alter linguistic patterns in host population. The study reveals that ethnic identity is controlled by hierarchal social forces contributing to how ethnic nationalism is prioritized (Semela, 2012). In contrast, it indicates that the use of common language may provide better opportunities for improved intercultural understanding. Sebastiana and Rajagopalana (2009) study of tourism development in Kerala provides and interesting example of the adoption of different foreign languages in order to communicate with tourists. This is an important lesson for Oman; because language training is useful towards welcoming tourists to a country and a reputation of a particular widely spoken language can result in increased travel by people from particular country. Social impacts and cultural impacts can be diverse, but Oman has the opportunity to look at what has occurred across the region so they can prepare and educate the population about business and entrepreneurial opportunities so locals can benefit from tourism and prepare for a sustainable future.

Concluding Remarks

This chapter addressed how Dubai’s tourism development and increased investment in tourism infrastructure have produced economic, environmental and socio-cultural impacts, with varying positive and critical positions. However, the content discussed in this chapter offer lessons for other cases across the Gulf Region. Given the regions strategic geographic location, it is important that tourism planners, government officials and policy makers work with business developers and local communities to develop a framework to plan for tourism growth based on triple bottom line impacts. Moreover, not only has the Emirate of Dubai provided an important lesson on how shifting towards tourism can result in economic growth, but it also provides a valuable lessons for an emerging tourism destination such as Oman. The model presented in Figure 1 outlines interactions among the three triple bottom line impacts pointing to the main critical points observed in this chapter. Other Gulf tourism destinations likely face similar critical issues and consequences and can learn from Oman’s approach to plan tourism accordingly to maximize social and environmental impacts and benefits aimed at planning for a sustainable future.

From this chapter, the key question is when tourism does increase in Oman, how will the destination respond and evaluate positive and negative impacts in Dubai. The points outlined above are based on findings, examples and discussions pointing to similarities and differences observed in Oman and Dubai. Although these destinations are regarded at different scales, the wider emphasis of tourism impacts can be evaluated across scales from the city, region, state and national levels. As global tourism increases and consumer trends and demands change, destinations such as Oman need to prepare for tourism to bring about economic and employment benefits whilst maintaining high environmental awareness standards and preserving culture and local/national identity. Because Dubai is a city and Oman a country, it is the wider lessons that have been found looking at Dubai that point to lessons for Oman, especially in Oman’s urban and hinterland tourism across the country. The studies on the impact of tourism on different cases from around the world have taught us that tourism development challenges a host populations environmental awareness and socio-cultural values. As such, the success of Dubai’s tourism model did not come without economic, environmental and socio-cultural drawbacks. In summary, in Dubai, the high number of migrant labourers in the private sector, the alteration of coastal areas, and the impact on Emirati culture and language are some indications of tourism’s adverse impacts. While these are unavoidable side effects of tourism, there are lessons learnt by assessing an established destination and an emerging destination. Therefore, if the Omani government recognises the importance of sustainable environmental planning and establishes business/enterprise initiatives that involve training and educating locals to consider environmental and cultural values, then constructive results could be achieved over the longer-term. Dubai, in this case represents a base to assess how rapid investments in tourism impact a destination putting Oman tourism officials, planners and policy makers in a unique situation to learn from observations outlined above. More immediately, tourism is needed to support job creation and new businesses opportunities, but the focus needs to be on local involvement in the industry as Dubai relies on people from abroad to fulfil service sector positions in the tourism and hospitality industry.

To conclude, despite the economic growth caused by the rapid development of tourism industry, many Dubai residents are unhappy with the lifestyle and habits associated with mass tourism and a larger international labour force. This is because they believe that tourism increases traffic and has a direct impact on losing their cultural identity. While, Stephenson and Ali-Knight’s (2010) suggest that the Emirati culture needs to be rediscovered and inclusive of the tourist gaze, it also questions the degree to which the locals are willing to expose themselves without risking being influenced by the western tourists. Therefore, the model of impacts based on the triple bottom line in Dubai gives Oman much to consider. Future research is needed to assess the points outlined in Figure 1 and to provide tangible and intangible evidence of the current situation of tourism development in Oman as the destination emerges.

Travel & Tourism Economic Impact 2018 (World Report)

As one of the world’s largest economic sectors, Travel & Tourism creates jobs, drives exports, and generates prosperity across the world. In our annual analysis of the global economic impact of Travel & Tourism, the sector is shown to account for 10.4% of global GDP and 313 million jobs, or 9.9% of total employment, in 2017.

The right policy and investment decisions are only made with empirical evidence. For over 25 years, the World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC) has been providing this evidence, quantifying the economic and employment impact of Travel & Tourism. Our 2018 Annual Economic Reports cover 185 countries and 25 regions of the world, providing the necessary data on 2017 performance as well as unique 10-year forecasts on the sector’s potential. 2017 was one of the strongest years of GDP growth in a decade with robust consumer spending worldwide. This global growth transferred again into Travel & Tourism with the sector’s direct growth of 4.6% outpacing the global economy for the seventh successive year. As in recent years, performance was particularly strong across Asia, but proving the sector’s resilience, 2017 also saw countries such as Tunisia, Turkey and Egypt that had previously been devastated by the impacts of terrorist activity, recover strongly.

For detailed analyses, read the report in here

TRAVEL & TOURISM GLOBAL ECONOMIC IMPACT & ISSUES 2018

download the report from here

As one of the world’s largest economic sectors, Travel & Tourism creates jobs, drives exports, and generates prosperity across the world. In our annual analysis of the global economic impact of Travel & Tourism, the sector is shown to account for 10.4% of global GDP and 313 million jobs, or 9.9% of total employment, in 2017. The right policy and investment decisions are only made with empirical evidence. For over 25 years, the World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC) has been providing this evidence, quantifying the economic and employment impact of Travel & Tourism. Our 2018 Annual Economic Reports cover 185 countries and 25 regions of the world, providing the necessary data on 2017 performance as well as unique 10-year forecasts on the sector’s potential. 2017 was one of the strongest years of GDP growth in a decade with robust consumer spending worldwide. This global growth transferred again into Travel & Tourism with the sector’s direct growth of 4.6% outpacing the global economy for the seventh successive year. As in recent years, performance was particularly strong across Asia, but proving the sector’s resilience, 2017 also saw countries such as Tunisia, Turkey and Egypt that had previously been devastated by the impacts of terrorist activity, recover strongly. This power of resilience in Travel & Tourism will be much needed for the many established Travel & Tourism destinations that were severely impacted by natural disasters in 2017. While our data shows the extent of these impacts and rates of recovery over the decade ahead, beyond just numbers, WTTC and its Members are working hard to support local communities as they rebuild and recover. Inclusive growth and ensuring a future with quality jobs are the concerns of governments everywhere. Travel & Tourism, which already supports one in every ten jobs on the planet, is a dynamic engine of employment opportunity. Over the past ten years, one in five of all jobs created across the world has been in the sector and, with the right regulatory conditions and government support, nearly 100 million new jobs could be created over the decade ahead. Over the longer term, forecast growth of the Travel & Tourism sector will continue to be robust as millions more people are moved to travel to see the wonders of the world. Strong growth also requires strong management, and WTTC will also continue to take a leadership role with destinations to ensure that they are planning effectively and strategically for growth, accounting for the needs of all stakeholders and using the most advanced technologies in the process. WTTC is proud to continue to provide the evidence base required in order to help both public and private bodies make the right decisions for the future growth of a sustainable Travel & Tourism sector, and for the millions of people who depend on it.

Economic diversification in GCC countries: Past record and future trends (2013)

Read Article from here

Abstract

Employing an empirical and comparative approach, this research paper analyses the past record and future trends of economic diversification efforts in the six Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. Applying the methodology of content analysis, possible future diversification trends are studied from current development plans and national visions published by the GCC governments. The past record of diversification has yielded only meagre results. Current development plans point unanimously to diversification as the means to secure the stability and the sustainability of income levels in the future. Even though the states continue to lead the economies, diversification entails a reinvigoration of the private sector and as such necessitates the implementation of broader reforms. The paper, however, questions the likelihood of diversification plans being translated into action. There are a number of structural barriers to diversification, which relate to the growth scenarios for the world economy, the duplication of economic activities among the GCC states, and, not least, the sizable barriers to interregional trade. Furthermore, the policy response to pre-empt the Arab Spring uprising indicates that these regimes easily give up their well-argued and planned policies when under pressure and fall back on established ways of doing business, namely through patronage and the predominant role of the public sector. Hence, the prospect of diversifying economies through politically difficult economic reforms has suffered a significant setback. This conclusion, however, does not rule out a piecemeal and ad hoc implementation of the diversification strategies in the future

Traditions of sustainability in tourism studies (2006)

Muslim World and Its Tourism (2014)

Read full article from here

Abstract

The study of tourism in the Muslim world can be about religious topics such as hajj and pilgrimage, but it actually means and involves much more. Because religious life and secular life in Islam are closely intertwined, study of its tourism is also partly about its worldview and culture as well as a means of reflecting on Western concepts of travel and hedonistic tourism. This review article introduces selected aspects of Islam to non-Muslims and reviews the tourism literature to identify themes and areas for further research. In addition to scholarly goals, an understanding of the patterns and requirements of the growing numbers of Muslim travellers is of practical importance for the tourism industry. Significantly, the Muslim world provides opportunities for studying differences in policy and development decisions that can offer new insights and inform tourism by providing alternative perspectives.

Study on managing the environment under mass tourism (2013)

Read full article from here

Abstract:

While tourism provides considerable economic benefits for many countries, regions and communities, its rapid expansion has also had detrimental environmental and socio-cultural impacts. Due to the dramatic development of tourism, the transport of passengers has been of major importance to socio-economic systems. This paper focuses on the negative environmental impacts resulting from mass tourism and transportation pollution. It cites some documented cases where it is applicable. It also provides an analysis of these factors as well. Finally, this paper gives some recommendations at all levels of responsibility. It proposes that the promotion of sustainable tourism development; internalizing social costs of environmental impact assessment (EIA); properly planned and public education are all essential parts for maximizing its socio-economic benefits and minimizing its environmental impact.

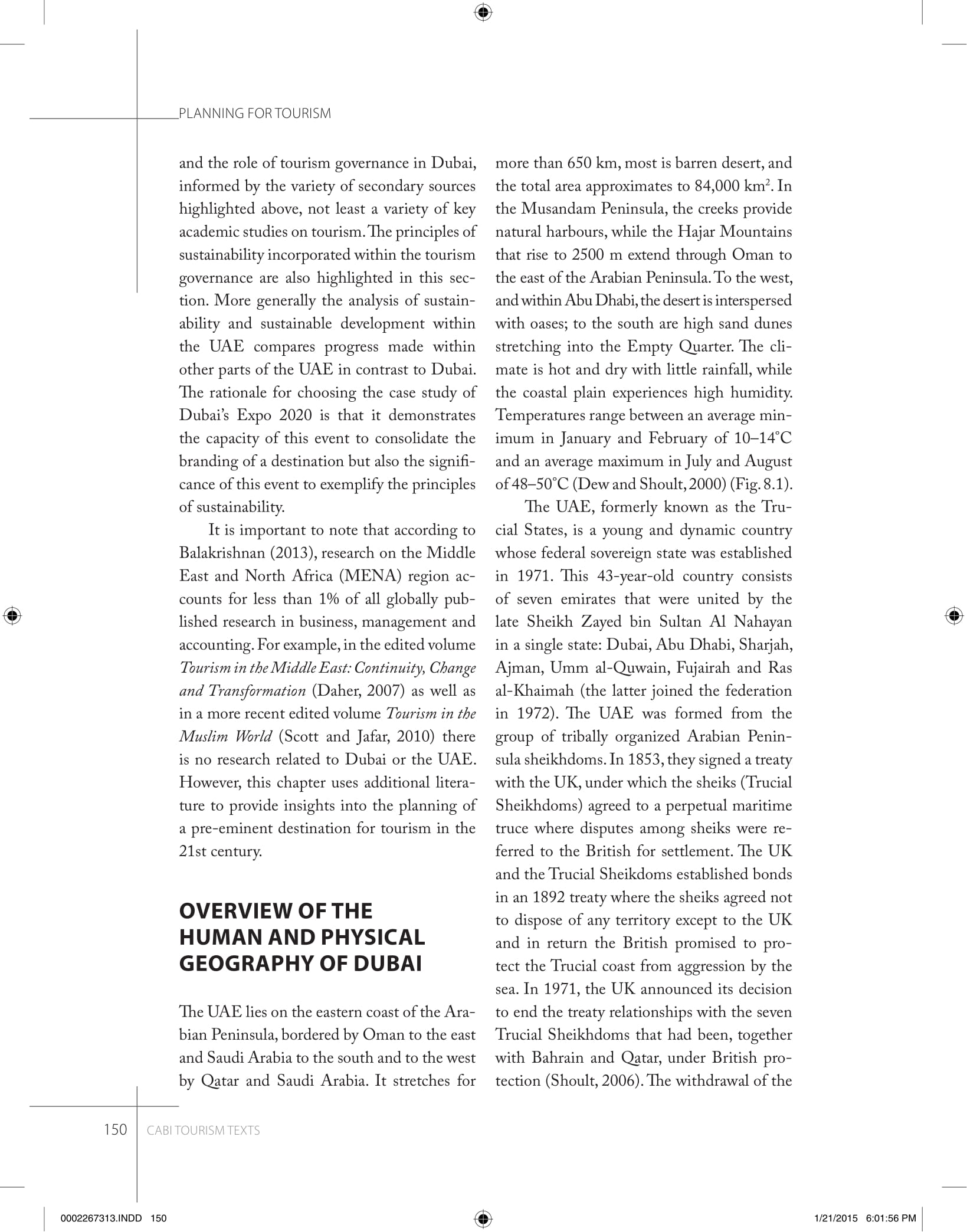

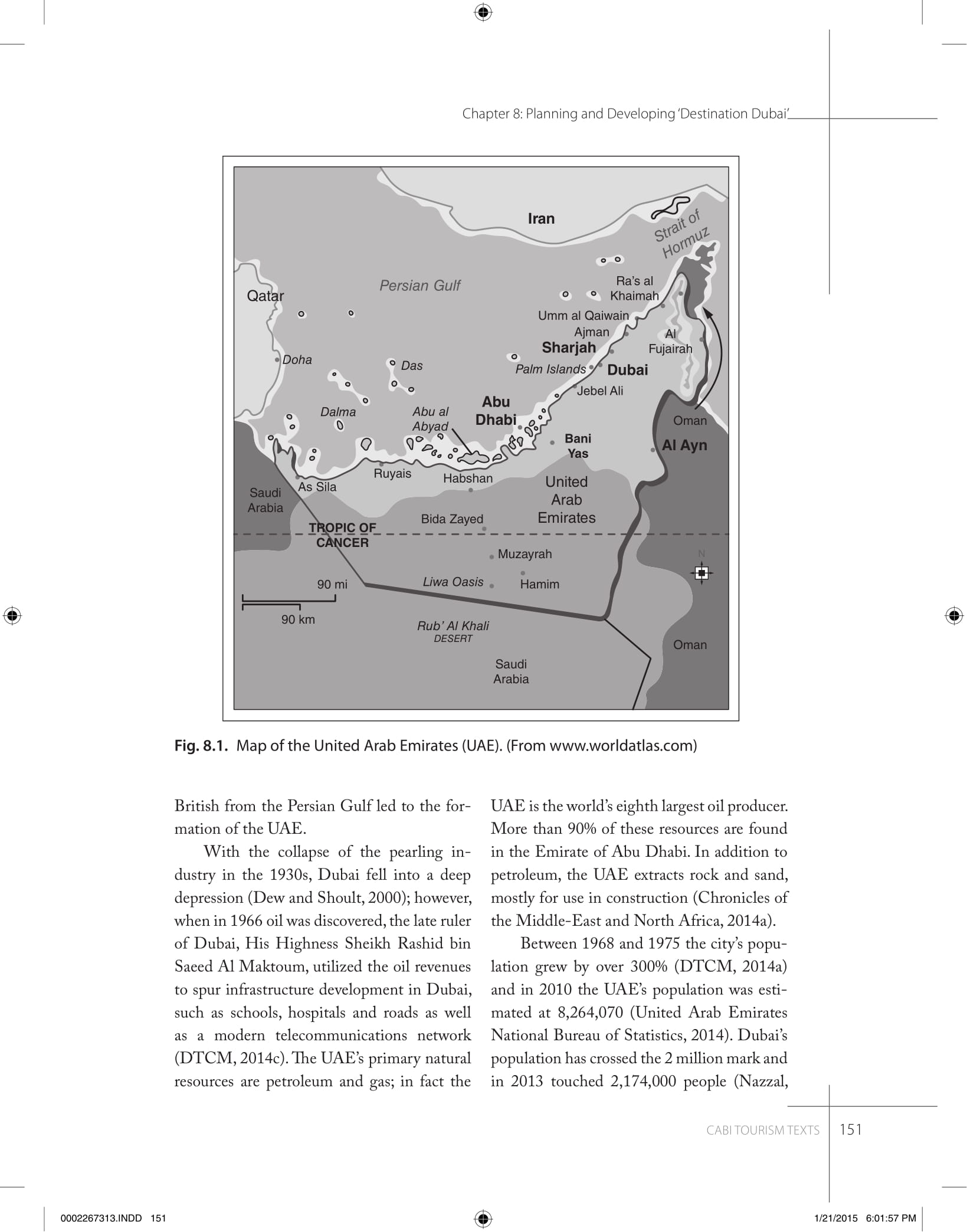

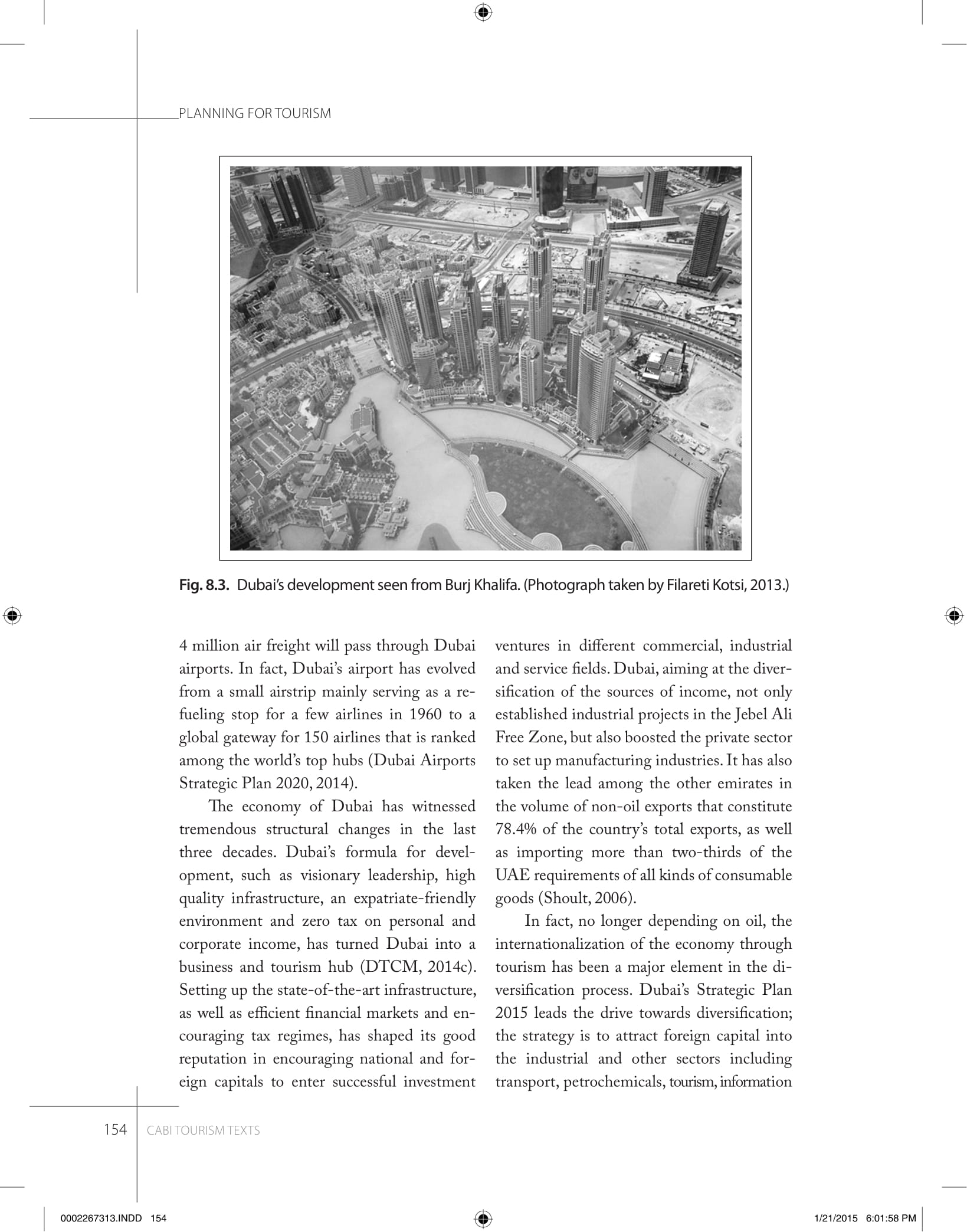

Planning and Developing 'Destination Dubai'in the Context of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) (2015)